On a bright summer morning in London, Alastair Moss acknowledges that there are more attractive locations for an interview than the Fleet Street offices of law firm Memery Crystal, where is he co-head of real estate. “We could have this meeting sitting in Guildhall yard,” he says. “Or on a bench out there on a roof garden, or on a terrace.”

Moss points this out not by way of an apology, but to highlight how much the streets, buildings and public spaces in the City of London have changed over the course of his career – a matter of years ago, those other options wouldn’t have been so easily available. And Moss, a lawyer by trade, is now closer to the changes than ever before, having in April taken chairmanship of the planning and transportation committee at the City of London Corporation, the body that governs the Square Mile.

His new role comes at a pivotal time for the built environment across the capital’s financial hub. The tallest tower the area has yet seen is close to completion at 22 Bishopsgate, with others approved. A 25-year transport strategy – the first of its kind signed off by the City corporation – has mapped out new ways to manage safer, cleaner streets. New initiatives are bringing public and private sector together, such as a partnership between the City corporation and property owners to help revamp Fleet Street.

But there are challenges to face, too. City firms are grappling with uncertainty around Brexit, particularly banks and other financial services firms trying to work out which jobs to keep in London and which to move elsewhere. And plans for some of the most ambitious buildings, such as the 300-metre plus Tulip viewing platform, have been scuppered.

If Moss feels pressure, he hides it well. Dressed casually in jeans, a shirt and jacket, he is relaxed during an hour-long interview about his vision for the City and its skyline, as well as the new approaches he wants the corporation and other local authorities to be taking to planning and development.

“It doesn’t really matter too much that the City’s structures are ancient in terms of governance, the fact we have committee structures or are in a very, very old building [at Guildhall],” he says. “You can still have a foot in the past but be looking forward.”

Talking across boundaries

Chairing the corporation’s planning committee is Moss’s latest role in local authority planning – he was deputy chair of the committee to Chris Hayward before and, earlier in his career, chaired the planning and city development committee at Westminster City Council. Like Hayward before him, Moss stresses the privilege that comes with a post in which you can leave a legacy in the form of bricks and mortar.

He also credits Hayward with pushing to get planning authorities in different boroughs working more closely together, something Moss wants to continue in his tenure as committee chairman. “No one cares about borough boundaries,” he says. “So why do we not speak to each other? [The City is] not an island state.”

He highlights work at the new Smithfield Market site for the Museum of London, where the corporation is including Islington council in discussions given the site’s proximity to the boundary between the borough and the City.

“We are liaising closely with Islington [council] as to what their aspirations are in that area because they are literally just a few metres away,” he says. “When people come in from across the world to visit the new Museum of London, they’re not going to go ‘that’s alright until after the City boundary’.”

But expect some friendly rivalry, too. The Square Mile has historically been home to bankers, insurers and other types of financial services professionals. As technology and media companies increasingly take office space, the area will more closely compete with other neighbourhoods and boroughs for location-agnostic occupiers, even if Moss insists that he does not see Canary Wharf, for example, as competing with the City for tenants.

During a discussion about the City of London’s ability to adapt in the face of challenges, Moss points to its physical survival of the plague, fires and the Blitz. Asked whether he thinks its ability to attract investment and development will now survive Brexit, he doesn’t blink.

“That’s absolutely for certain – I don’t think there’s very much to survive with that,” he says. “In terms of the built environment, this is still an extremely stable place to invest and to occupy… there’s uncertainty, clearly, but that’s not stopping the overall argument.”

The City’s status as one of the world’s leading financial centres is central to the City corporation’s existence, Moss says – and so banks, insurance companies, professional services firms and other traditional tenants must remain looked after.

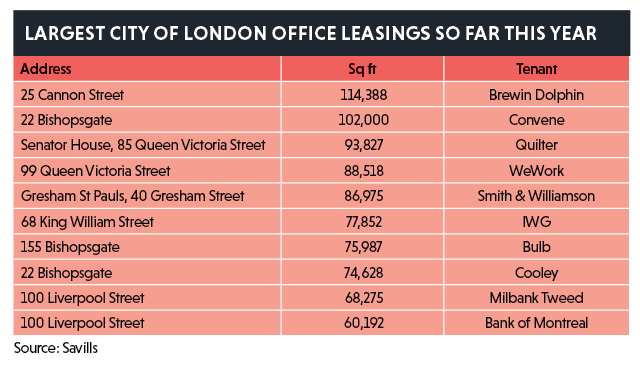

But Brexit’s threat to the City’s traditional occupier base of banks and fund houses means the importance of attracting other types of occupier will increase. Just four of the largest office leasings agreed in the Square Mile so far in 2019 have been to financial services companies.

“I’m determined the City will be seen as more diverse and more interesting,” says Moss, arguing that the focus has to broaden from solely “people in pinstripe suits walking down Lombard Street” to take in initiatives such as the Culture Mile, a stretch of the City between Farringdon and Moorgate that the corporation wants to become a hotbed of “culture and creativity”.

Moss goes on: “We’re not trying to make this place into the West End. We’re not trying to make it into Canary Wharf. We’re not trying to make it into Spitalfields. It should have its own kind of dynamics and personality, which tallies with the world-class talent we’re trying to get in.”

Cut down to size

Moss returns frequently during conversation to his desire for the City, its buildings and infrastructure to be more “radical”: pushing the boundaries of how environmentally friendly an office can be, for example, or built to appear unlike any other addition to the skyline.

Was the Tulip a step too far? The Foster + Partners-designed attraction, which would have included viewing floors, a restaurant and bar and classrooms for schoolchildren, was approved by the City corporation’s planning committee in early April. But London mayor Sadiq Khan ruled in July that its design would be detrimental to the skyline and protected views of the Tower of London, adding that “the public benefits of the scheme are limited and would not outweigh this harm”. The plans were rejected.

Moss stands by his decision to vote for the project. “I have no concern about the effects it would have had,” he says. “I think it would have only had positive effects. The role of a good authority is to weigh up the advantages and disadvantages, and my personal view is that in a rare occasion our views and the mayor’s diverged there. I think it’s that simple difference of opinion as to what the public benefits are.”

He continues: “Our relationship with the mayor matters. Our relationship with developers matters. The City is open for business, notwithstanding the fact that occasionally what we think is the right thing and appropriate, others may not think is.”

One of Khan’s criticisms of the Tulip was that it would create crowds on the narrow pavements of the City, making the area more dangerous for pedestrians. Moss may not agree with the cancellation of the project, but he will at least understand concerns over safety on the city’s streets.

The transport plan presented to the planning and transportation committee back in May outlined schemes to make the area around the cluster of City towers greener, as well as developing zero-emission zones to improve air quality and limiting traffic.

Nowhere have traffic calming measures had greater impact than at the junction by the Bank of England. Roads there have been closed to all traffic other than buses and bicycles for much of the working day since May 2017.

The City corporation’s “All change at Bank” initiative is now helping the corporation explore even more radical alterations to that landmark part of the Square Mile, including pedestrianising the junction entirely. Moss knows that the potential changes are massive steps in terms of how the City works, but he also believes they are worth it.

“That is extremely controversial as a scheme – to be closing roads, to be disrupting how people live their lives,” he says of changes at Bank. “How do you get into your office? How do you have your deliveries if you’re a sandwich shop? You’re asking people to make sacrifices. But I feel very strongly there is a duty on us to deal with those things, because they’re directly health related.”

That focus on wellbeing and the people that fill the City’s tall towers is at the heart of the corporation’s work, Moss says, regardless of which buildings are approved or not.

“The City is about the people,” he adds. “And the real estate sector has quite rightly picked up on that. The buildings, the environment, are all there to basically serve us and we’re stewards and custodians. But it’s about the people that we want to attract and retain across the world to be a really great place to be.”

To send feedback, e-mail tim.burke@egi.co.uk or tweet @_tim_burke or @estatesgazette