It is not the auspicious sign supporters of the Northern Powerhouse were hoping for. Last month the government agreed with an independent planning inspector that the plug should be pulled on a proposed £250m trolleybus system for Leeds.

It is not the auspicious sign supporters of the Northern Powerhouse were hoping for. Last month the government agreed with an independent planning inspector that the plug should be pulled on a proposed £250m trolleybus system for Leeds.

Known locally as New Generation Transport, it had been in the planning pipeline for the last nine years. This is the second time that a mass transit system for the city has hit the buffers, after a £1bn, 17-mile tram scheme was knocked on the head back in 2005.

On this occasion, secretary of state for transport Patrick McLoughlin said in a letter that he “agrees with the inspector that, on the basis of the evidence examined at the inquiry, the ability of the NGT scheme to deliver the level of transportation and socio-economic benefits that the applicants have predicted has not been substantiated”.

Although £174m allocated to NGT will be ring-fenced for other Leeds transport improvements, this is a bitter blow for a city that has spent £27m on the project (and £40m on the aborted tram system). Keith Wakefield, chair of the West Yorkshire Combined Authority’s transport committee, responds that the refusal “is a frustrating reminder that despite the government’s emphasis on devolution, we still find ourselves subject to decisions made remotely in Whitehall on local matters”.

This certainly wasn’t in the script when, last spring, a posse of politicians (including McLoughlin) gathered with great fanfare to launch the first Northern Transport Strategy (see below). And it must stick in Leeds’ craw that Manchester’s Metrolink tram network has been consistently successful since it started running in 1992.

Striking a balance between developing individual city networks and joining the dots between the core centres of the Northern Powerhouse will be one of the biggest challenges for umbrella organisation Transport for the North. Although Manchester is pre-eminent, other cities also have successful mass transit systems: Newcastle’s Metro is now 36 years old (and in need of some attention), while Sheffield’s Supertram, which opened in 1994, plans to pioneer a tram-train operation to Rotherham next year.

While there has been plenty of talk of transport improvements, action has so far been in short supply. Muse Developments’ joint managing director Matt Crompton sums up the view of many in the property sector: “Transport infrastructure is absolutely prime. I think they’ve got a good plan, they just need to get on with it.”

Hiro Aso, regional head of transport and infrastructure at architect Gensler, agrees: “We need to push forward with changes and quickly. Otherwise, we’ll be learning lessons from elsewhere in the world if we continue just to strategise about what needs to be done as the property market is demanding it.”

Even if work starts quickly, it will need to be targeted carefully within the Northern Powerhouse, warns Simon Sherwood, Leeds-based partner at law firm Mills & Reeve: “There is a real risk that without integration and inclusion of the smaller centres, the major centres of the North will simply do well at the expense of many of the rest.”

For now, the property market is getting more excited about the prospect of a constant mobile or WiFi connection while travelling across the Pennines by train than some of the more distant goals outlined in the Northern Transport Strategy.

“The market tends to take a lukewarm view until something becomes a firm commitment,” confirms Iain Jenkinson, senior director of CBRE’s Manchester office. “However, investors and developers definitely think transport hubs are a prize worth going for as they can mean a 20% increase in values.”

Energy coast has the power

One thing the Northern Powerhouse will require plenty of in the next few years is, well, power. Questions about where electricity will be generated, how it will be decarbonised and how it will be distributed effectively and efficiently across the region have so far been low-key and largely in the domain of politicians.

Developers aren’t flagging up concerns about grid connections and engineers suggest that, as long as local authorities take a lead in delivering localised energy, there should be no risk of the lights going out anywhere between Newcastle and Liverpool.

An energy hub is evolving in West Cumbria, locally referred to as the Energy Coast. Plans are in place here to build up to 10GW of new generation capacity – that’s around 10% of the UK’s total energy requirements. Extra capacity at Sellafield, a new nuclear power station at Moorside, a tidal barrage, and expansion of wind turbines in the Solway Firth should provide plenty of low-carbon juice for the future.

Paul Yates, client director at engineering consultancy Atkins adds: “We’re also expecting to see further advances in waste to energy and local generation connected to heat networks in the region. These are all incredibly exciting opportunities for building a diverse energy mix in the Northern Powerhouse.”

Broadband lottery

While quicker train journeys may be a prospect for the Northern Powerhouse, the arrival of faster broadband is less certain. A recent survey (see table below) revealed that centres in the northern powerhouse both topped and bottomed a league of 42 major UK centres. Only two of the top 10 are in the powerhouse area – but possibly not the centres one might expect: Middlesbrough (fastest average UK speed 34.46Mbps) and Huddersfield. Major business hubs come lower down the list: Liverpool (12th), Leeds (15th), Manchester (23rd) and Newcastle (34th).

Contrary to popular expectations, London doesn’t rate highly, coming in at 28th place with a speed of 22.44Mbps. The survey is considered significant in that it shows a snapshot of how broadband is actually being taken up, rather than stating theoretical maxima.

Average broadband speeds are only part of the picture and higher speeds are available in key northern powerhouse cities for businesses that are prepared to pay for them. Even here, however, there are concerns. Research by Deloitte last autumn came to the staggering conclusion that no key business locations in the North West have access to superfast broadband as standard and describes connections in the regions as a lottery.

Average download speeds – selected Northern Powerhouse centres v London

| Position | City | Speed |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | Middlesbrough | 34.46 |

| 8th | Huddersfield | 27.71 |

| 12th | Liverpool | 26.60 |

| 15th | Leeds | 26.18 |

| 23rd | Manchester | 23.81 |

| 28th | London | 22.44 |

| 34th | Newcastle | 21.14 |

| 42nd | Hull | 12.42 |

Jodi Birkett, TMT partner at Deloitte, says: “With the rise of cloud computing, the need for high internet speeds has become more acute and a slow connection can have a serious impact on business productivity. The state of play in Manchester and Liverpool doesn’t make for good reading and it needs improving if we want to create a true northern powerhouse.”

Deloitte analysed 12 business locations in the North West, including Spinningfields, Old Hall Street and the major Manchester science parks, and found that only one-third have access to partial high-speed fibre optic broadband, while none have access to the fastest fibre-to-the-premises (FTTP) connections.

Yet property people are largely sanguine on the issue. Matt Crompton, joint managing director of Muse Developments, reports that he has encountered “no issue with broadband” at any of the developer’s projects across the Northern Powerhouse.

Transport hotspots for property

• Mayfield Quarter, Manchester: Any time now a development partner will be chosen by landowners London & Continental Railways, Manchester City Council and Transport for Greater Manchester to take forward the regeneration of land around the former Mayfield Railway station. Carillion, Ask and Patrizia Consortium, Urban & Civic and U+I are all on the shortlist to build out up to 800,000 sq ft of offices and 1,300 homes which will sit next door to Manchester’s HS2 station at Piccadilly, due to open by 2033.

• South Bank, Leeds: The trolleybus scheme may have been cancelled, but HS2 is very much still heading for Leeds. A rethink over the station location – now to be integrated with the city’s existing rail hub – has been broadly welcomed and is likely to create the opportunity for new office development on the 320-acre South Bank site, as well as the wider area around Leeds City station. It is likely that a masterplan will be drawn up to allow for strategic development of the area before the high speed trains arrive in 2033.

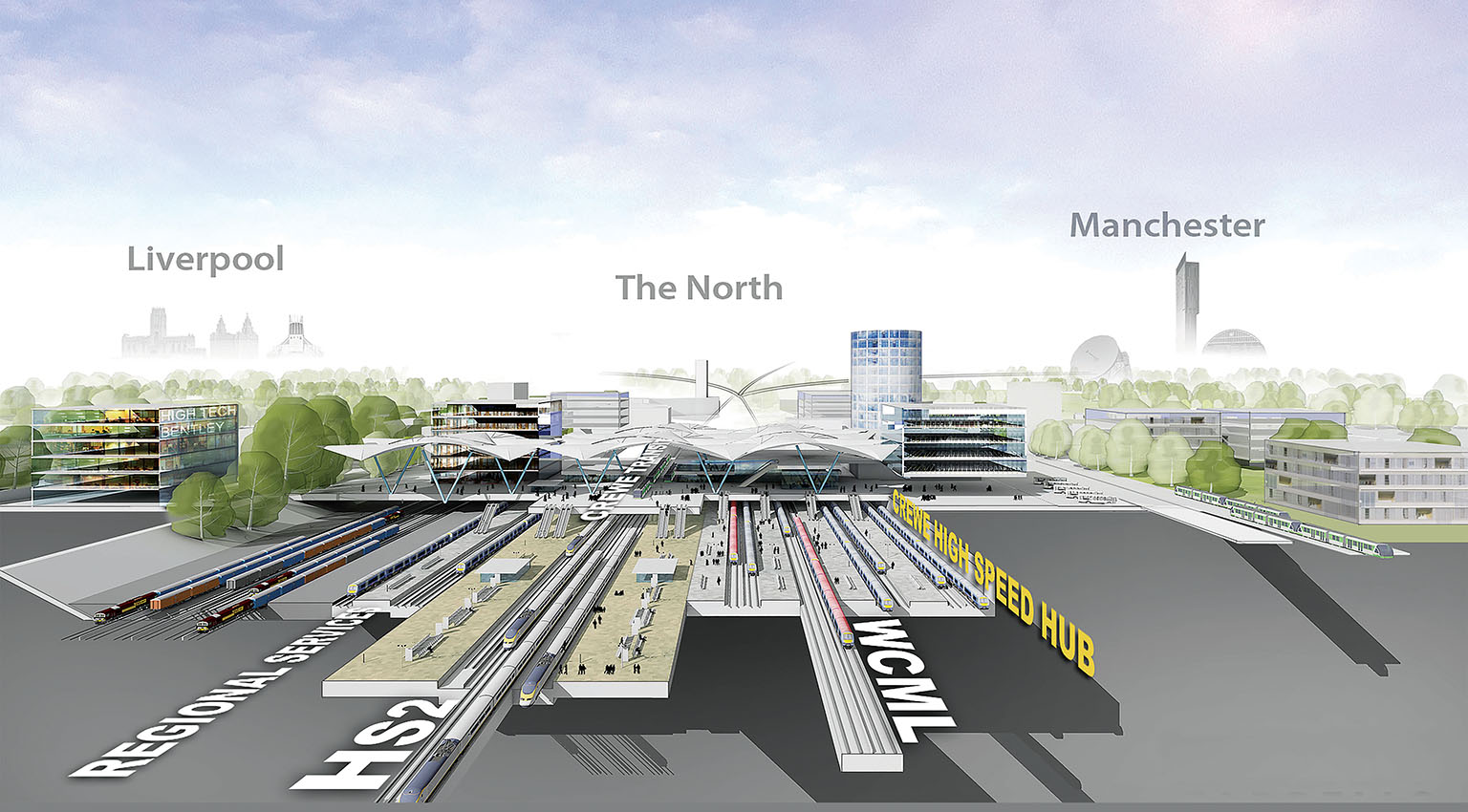

• City centre, Crewe: The surprise announcement last winter that part of the second phase of HS2 (now known as 2a) between Birmingham and Crewe will be brought forward to 2027 is likely to bring a renaissance to the town that was originally created by the railway 175 years ago. A new hub station, whose exact location is still to be agreed, is likely to act as a catalyst for major commercial property development. Local authority Cheshire East council is to set up a regeneration company to oversee plans for the area.

Northern Transport Strategy

In March, Transport for the North, the body linking transport authorities in the region, marked the 12 months since it set out its Northern Transport Strategy with a 64-page report outlining progress made so far. Understandably, attention in the past year has focused on thinking rather than doing, but even so, reaction to the report (and TfN itself) from the property community has been mixed.

“I think it’s got the balance right between funded projects that are happening now and feasibility studies for things like HS3 and the trans-Pennine tunnel that may happen in 20 years’ time,” reckons Cathy Wignall, urban strategist at Deloitte in Manchester.

John Francis, director of planning consultancy DPP’s Manchester office, is more sceptical: “TfN probably won’t work until you create a tier of governance to match it. Something along the lines of the Scottish model, but with more power. It also needs a 50-year plan, but what government will commit to that?” he questions.

There is widespread recognition that TfN is likely to initially prioritise projects that can provide demonstrable results on the ground reasonably quickly.

“When they run out of the easy wins, they will have to consider which bigger picture projects are most likely to get support,” says Andrew Batterton, Leeds-based partner of law firm DLA Piper.