When consent was given last week for Network Rail’s plans to redevelop Brixton Arches, protesters came out in force. Janie Manzoori-Stamford looks at the issues surrounding Brixton’s gentrification

Nothing livens up a planning meeting like a glitter bomb. A shower of blood-red sparkles raining down amid catcalls of angry protest is a far more spirited conclusion to nearly three hours of discussion than a call for any other business. Especially when it is followed by the arrival of several uniformed police officers, drafted in to keep the peace. So very bohemian, so very Brixton.

This is exactly what happened last week when Lambeth Council’s planning committee meeting, held in public at the Karibu Centre on Gresham Road, SW9, voted six to one in favour of proposals to redevelop the railway arches beneath Brixton rail station. The site is currently home to an eclectic mix of independent traders, including a fishmonger, carpet seller and hair salon.

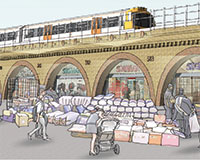

Landlord Network Rail says it aims to “enhance the character and improve the fabric and structural integrity” of the arches. Over the course of a 12-month, £8m revamp beginning at the end of this month, it says the plans will rejuvenate an important part of Brixton’s cultural heritage.

New shop frontages, 26 re-clad units and 13 new kiosks are among the plans to improve the “commercial attractiveness” of the arches which the public sector body says will bring them in line with other Brixton retailers, increase footfall and help boost the local economy.

But not everyone is on board. Apart from the glitter bombing protesters, a petition objecting to Network Rail’s proposal has attracted nearly 30,000 signatures. This is just one chapter in the ongoing debate around gentrification in London – for which Brixton has become the poster child. So just how could the transformation of such an historic fixture on Brixton’s retail landscape contribute to the on-going debate around pros and cons of “premiumisation” in London?

At what cost?

On paper, the arches scheme looks to have real potential to boost regeneration efforts in an area that has in the past been known for crime and poverty.

Back in 2001 the centre of Brixton was described by a police chief as a “24-hour crack supermarket”. These days the visitors it attracts from across London are more likely to be there for a gourmet burger or a craft beer in the thriving food and drink hub of Brixton Village, housed in three bustling arcades that were previously home to covered markets.

And as Brixton’s desirability has shot up, so too have house prices. Residential property values have increased by 128% in the last 10 years, with the average price of a semi-detached house in Brixton now topping £1m.

The cost of renting also shows how far Brixton has come. On average, a one-bedroom property in Brixton rents for £1,744 pcm (up by 23% year-on-year), just £43 less than nearby and traditionally more affluent, Clapham, according to Zoopla. It is certainly a positive story from a landlord perspective, but at what cost?

Network Rail says that to achieve its refurbishment ambitions, it needs to terminate the leases of the current occupiers. Around 30 independent traders and tenants, many of which have occupied and worked out of

the space for upwards of 25 years, are to be evicted on 19 August. And they are not happy about it.

“When Brixton was bad, we were good,” says Riccardo Festa, who owns menswear store The Baron, which his grandfather opened on the Atlantic Road side of Brixton Arches in 1974. “But now that Brixton is good, we are bad.”

Festa, who has around 11 years left to run on his 20-year lease, is convinced that his landlord wants the current occupiers out because more money can be made from new tenants. And this is despite an offer by Network Rail to return to a refurbished arch – not necessarily the same one that was vacated – after works complete, with discounted stepped rents over seven years.

This means that the 2015 market rate, which Network Rail has determined as being more than double what tenants currently pay, will not be imposed on returning occupiers until 2024. It is a strong offer and one that the company says it does not do anywhere else. But is it affordable?

“They just don’t want us here. If they have us back once the work is finished, they are going to get less rent,” says Festa. “How can any business go from paying £22,000 to just under £70,000 in five years? It is financially impossible. Does that mean I am going to get three times the trade?”

As such, Festa and his fellow traders believe the units will be let to multinational businesses that can afford the steeper rent, a claim that their landlord has repeatedly denied.

Matthew Ball, senior public affairs consultant for Network Rail’s commercial estate, says: “We have got 7,500 units in London and fewer than 20 chains in any of those. If we are not the largest landlord to small- and medium-sized businesses in the UK, we are certainly up there. That is something we are very proud of.”

Network Rail says its property team is conscious of the need to be competitive but highlighted the importance of securing a fair return for the public sector body.

“It is an £8m investment from Network Rail and the scheme has to wash its face. We are a taxpayer-funded organisation,” he says. “Everything we do has to make a return in some way, otherwise we are effectively spending money that isn’t ours.”

It is a pragmatic approach, no doubt influenced by the increasing scrutiny of the company’s finances.

When Network Rail was in effect renationalised in 2014, its £38bn of debt was moved to the government’s already huge balance sheet. The pressure to drive down this debt led to last year’s appointment of investment bank Rothschild, which was tasked with assessing the rail firm’s £1bn commercial property portfolio.

In March 2016, it was reported that 18 of Britain’s landmark railway stations, including London Waterloo, Paddington and Birmingham New Street, could be sold off to help cut the debt.

This was followed by the formation of Network Rail Property, a business dedicated to maximising the value of the company’s estate. A £1.8bn sale of 7,500 other properties, including freight yards, car parks, arches, depots and spare land, is also on the cards.

Does that mean Brixton Arches might hit the market at some point? Possibly, but not as a standalone asset.

“Any disposal of the estate, if it goes ahead, will be as one entity. My understanding is it will not be broken up,” says Ball.

Brixton through the ages

Images: REX/Shutterstock

Regeneration or gentrification?

But the objections to Network Rail’s plans goes beyond what they mean for the retailers directly involved. It taps into a broader concern that Brixton is fast becoming the ultimate example of gentrification.

The soaring cost of living in this historically cheap area of London is making it increasingly unaffordable to long-term residents and commercial tenants are feeling the cost too. Last year saw Kaff, a popular café/bar on Atlantic Road, forced to close its doors after four years of trading because its landlord had tripled the rent.

This squeezing out of the old, to make way for a more wealthy new, has led the most extreme voices to say it is tantamount to social cleansing. And it is a sentiment that came to an angry head during a “reclaim Brixton” demonstration last year that saw protesters storm Lambeth Town Hall and smash up a branch of estate agent Foxtons.

But Network Rail insists that gentrification has no bearing on its motivation to carry out the works. It says it was driven by a need to carry out a full structural examination of the arches.

“We certainly don’t see this as gentrification,” says Network Rail. “We see it as an investment to not only improve our property but also to offer businesses in Brixton somewhere good that they can set up. We have got 13 kiosks going in that smaller-scale businesses, and even start-ups, will find useful. We are all about that and improving what we can offer to the community. It is not about any form of social cleansing at all.”

Brixton Arches is, according to Ball, one of the biggest development projects that Network Rail has undertaken for some time. But he maintains that the company recognises why the people of Brixton and beyond have such affection for them and, in particular, the traders that have served them for so many years.

“That’s why we have invested in seven years of stepped rent. And there is compensation for tenants whether they choose to leave or leave and come back, which is way above our statutory obligations,” he says.

“We are investing in that community to enable it to return and that is in line with the council’s strategy. That is why they granted planning permission 6-1, to be honest.”

The company is tight-lipped about how much compensation is being offered to the traders, but it is believed to be on average between £15,000 and £20,000 each. The discounted rent means that the company stands to lose around £150,000 per unit between 2017 and 2024.

Network Rail’s measurements of success for the project are clear, but for Brixton it is also about the preservation of the traders that have served their community for many decades.

They are part of the lifeblood – as vibrant and red as the protesters’ glitter – that runs through this corner of the capital to make it so bohemian. And so Brixton.

• To send feedback, e-mail Janie.Stamford@estatesgazette.com or tweet @JanieStamford or @estatesgazette