Stretching to 220 pages – and that’s before an index of financial statements – We Company’s prospectus for its long-awaited IPO is being pored over by the property community for insights into the business and balance sheet of the posterchild for the co-working craze.

The document, logged with the Securities and Exchange Commission, is packed with the usual purple prose expected from a company trying to convince equity investors to hand over their money.

“We are reinventing the way people work and transforming the way individuals and organisations relate to the workplace,” WeWork says. (Yes, the group has rebranded to The We Company as a corporate entity, but good luck finding anyone who refers to it as anything other than WeWork.)

“When we started, it was obvious to us that the solutions available in the market were not meeting the needs of the modern workforce and did not offer the community, flexibility and global mobility that individuals and organisations needed to grow and succeed.”

But beyond that, it is arguably the first chance since the company’s bond issuance to dive into the numbers. Here are some highlights.

1. WeWork is losing a lot of money…

The fact that WeWork is making a loss is news to no one. But the prospectus is a hotly anticipated chance to dig into the financial figures.

Revenues at WeWork Companies, The We Company’s predecessor, rose from $436m in 2016 to $886m in 2017 and $1.8bn last year. But pretax losses too have rocketed over that period – from $429.6m in 2016 to $939.2m in 2017 and $1.9bn in 2018.

Over the first half of this year the company posted an $899.5m pretax loss on revenues of $1.5bn, compared to a $724.2m loss on revenues of $763.7m a year earlier.

2. …but it could turn a profit if it felt like it. Maybe?

WeWork claims profitability is a “managed outcome”, based on how long a site has been open.

When a site has been open for two years, the company says it is considered “mature”. At that point: “Occupancy is generally stable, our initial investment in build-out and sales and marketing to drive member acquisition is complete and the location typically generates a recurring stream of revenues, contribution margin… and cash flow.”

As long as the company is prioritising what it calls “rapid growth”, it says, most of its sites will not be at this stage. As of the end of June, only 30% of its sites globally were considered mature.

But if the management team pivoted away from its focus on expansion, the bottom line would move into the black faster: “If we stopped investing in our growth and instead allowed our existing pipeline of locations to mature, we would no longer incur capital investments to build out new spaces or the initial expenses associated with driving member acquisition at new locations.”

3. This is a risky business

Any IPO prospectus outlines the risks a business faces as it prepares for life on the public markets. But WeWork’s walk through its red flags makes for sobering reading.

Most bluntly, the company notes: “We have a history of losses and, especially if we continue to grow at an accelerated rate, we may be unable to achieve profitability at a company level… for the foreseeable future.”

The company has emphasised that it can choose to slow down its investment in growth to prioritise profit at any time, but the section of the prospectus discussing risk does not read like this is on the cards, especially when it warns that losses will grow in the near term and “may increase as a percentage of revenue”.

“Our accumulated deficit and net losses have historically resulted primarily from the substantial investments required to grow our business, including the significant increase in recent periods in the number of locations we operate,” the company says.

“We expect that these costs and investments will continue to increase as we continue to grow our business. We also intend to invest in maintaining our high level of member service and support, which we consider critical to our continued success. We also expect to incur additional general and administrative expenses as a result of our growth. These expenditures will make it more difficult for us to achieve profitability, and we cannot predict whether we will achieve profitability for the foreseeable future.”

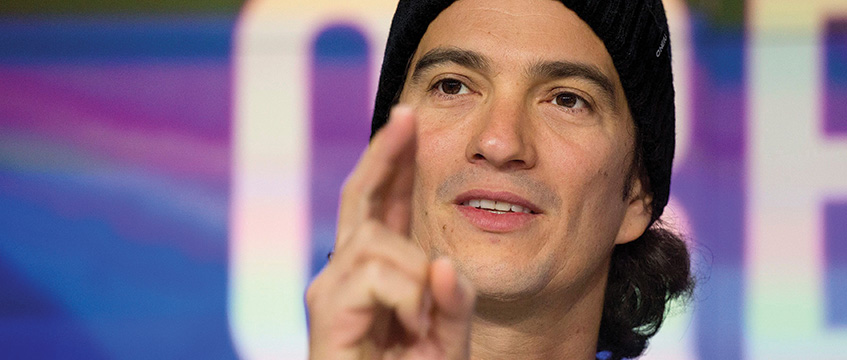

4. Adam Neumann is the key man – and investors should hope he chooses to stick around after the IPO

Co-founder Adam Neumann will control a majority of voting power at the company after the IPO, according to the prospectus. In the “risk factors” section of the prospectus, the company says that its success depends “in large part” on the chief executive sticking around post-listing.

“Our co-founder and chief executive officer is critical to our operations,” the company says. “Adam has been key to setting our vision, strategic direction and execution priorities. We have no employment agreement in place with Adam, and there can be no assurance that Adam will continue to work for us or serve our interests in any capacity. If Adam does not continue to serve as our chief executive officer, it could have a material adverse effect on our business.”

5. More than half of WeWork members are now outside of the US

The company’s international expansion has been rapid. In 2010, it ran two locations in New York. Now it runs 528 sites in 111 cities across 29 countries.

“In 2014, we made a bold decision to expand internationally to cities around the world while simultaneously building our brand and presence in the United States,” the company says. “We started in London, followed soon after by Tel Aviv, and by 2016, we had opened our doors in Shanghai, the first of our locations in Asia, as well as in Mexico City, the first of our locations in Latin America.”

The company now says it plans to grow “aggressively” in its existing cities as well as 169 cities in which it does not currently have a presence. In its existing cities, the company reckons it has an “addressable market opportunity” of $945bn, based on average revenues per member and data on desk jobs in those cities. Add in the other cities that the company is eyeing, and that number rises to a whopping $1.6tn.

6. WeWork really wants you to focus on its tech

WeWork is, at heart, a property company. But it pins the biggest savings it claims it can help tenants make on its tech.

“Technology is at the foundation of our global platform,” the prospectus says. “We have approximately 1,000 engineers, product designers and machine learning scientists that are dedicated to building, integrating and automating the complex systems we use to operate our business.”

The company reckons tenants can save up to two-thirds of costs per employee by basing themselves in a WeWork office, compared to taking a standard lease with build-out and operation costs.

7. Anyone who’s anyone on Wall Street and in the City is on board

The list of investment banks helping WeWork launch on the public markets reads like a who’s who of top financiers from Wall Street and London.

JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs are leading the team of underwriters on the equity offering, which also includes Bank of America, Barclays, Citigroup, Credit Suisse, HSBC, UBS and Wells Fargo.

Those same banks are lining up a fresh $6bn in debt financing for the company, part of which will be dependent on the IPO raising at least $3bn. Watch this space.

To send feedback, e-mail tim.burke@egi.co.uk or tweet @_tim_burke or @estatesgazette