Potent Whisper, rapper, and artists’ and community organiser, provides a comment to fuel the debate on housing estate regeneration

I have been asked to comment on why residents often oppose estate regeneration and how I feel the process could be improved. My thoughts, I am told, will form part of a debate between residents/communities and the developers that deliver regeneration schemes.

While I welcome the opportunity to share the experiences of those who have suffered under the shiny guise of regeneration, it strikes me as odd that the developers involved in this debate – the same developers who have displaced thousands of people and destroyed communities across London – now wish to look at how the process could be improved. Either the developers have suddenly developed a conscience, or this debate serves as nothing more than an opportunity to paint themselves as good corporate citizens who care about more than just profit.

It is crucial to begin by highlighting that the question of how the process of regeneration can be improved assumes that the process must take place at all. The answer to the question is assumed to be a foregone conclusion and takes into account no alternatives to demolition.

But this is not the case.

For example, residents at Cressingham Gardens estate, SW2, who are currently threatened with demolition, offered viable alternatives to the regeneration of their estate in the form of a “People’s Plan”. This consists of innovative solutions that would enable both refurbishments across the estate, which often come as a result of Lambeth’s managed decline, and the construction of 37 homes, which could largely be offered at council rents. And this could all take place without uprooting the community or pressuring the housing list.

The plan has been developed by the residents with technical support from a team of architects, surveyors, sustainability and financial experts as a realistic alternative to the proposed regeneration, which will cost £130m, compared with the £7m required for necessary refurbishments.

The People’s Plan is clearly a better option on every level, yet it has been dismissed by Lambeth Council, which instead chose to demolish the community of 300 families. The council claims it cannot afford new roofs, kitchens and bathrooms, despite having collected 40 years’ worth of rent and receiving more than £100m from the Decent Homes Standard fund.

In addition to considering the need for regeneration, the desire for it – or antipathy towards it –should also be taken into consideration. I am not alone in my belief that residents should have the right to be consulted properly on the proposed regeneration of their estate and I do not feel it unreasonable to demand that they are given a real say on something as immediate as the demolition of their homes.

Box-ticking exercise

Tragically, community consultations have become nothing more than an empty box-ticking exercise, with the wishes of residents more often than not being completely ignored.

At Cressingham Gardens, 86% of residents voted for refurbishment and only 4% for demolition. A vote on the Aylesbury Estate reflected a similar result. An official ballot, facilitated by the council, prompted a 76% turnout, with 73% voting against demolition and instead for refurbishment. People wish to remain in the homes that they love, the homes in which they have raised their families, alongside their neighbours, who are in many cases their support system and lifelines.

Councils and big corporations such as Network Rail also demonstrate their contempt for democracy when they decide the fate of local businesses. This was evidenced most recently in the case of the redevelopment of the Brixton Arches, where 30 tenants were evicted despite 950 people registering official planning objections, and 15 people supporting the redevelopment. Again, the wishes of the community and those being affected directly were overlooked.

To many people the word regeneration has a positive air about it. The word is associated with progress and newer, better things. For this reason people who oppose regeneration or the redevelopment of an area are often portrayed as backward thinking or against change. Change is indeed the basis of all history but when communities are represented by individuals who place personal profit before the welfare of their people, when our homes are stolen and then sold to the highest bidders, when an area is colonised economically and its people then suffer, we find ourselves asking whether this is the type of change we want.

Another false narrative is that residents who oppose regeneration must be “happy to live in squalor”. This narrative reveals the way in which much regeneration is framed: social housing estates are “dirty places” that are not fit for purpose and need (social) cleansing. This is sadly reflected in terms like “sink estates” or more shockingly “brownfield estates”. Our homes are viewed as waste and we are viewed as disposable.

Developers employ this type of language to justify regeneration, which many are taught to believe will better the lives of the residents on the estates. Tragically, some residents, usually tenants, are tricked into believing this too. The truth is the opposite. To a resident living in a council housing estate, the prospect of having their estate regenerated will mean one of four things.

The four effects of estate regeneration

Displacement or homelessness: Leaseholders will typically be served with a compulsory purchase order and forced to sell their home for a fraction of what it is worth. The amount they receive is too little to enable them to purchase another property in the area and they are therefore forced out of their community, and often out of London altogether.

Tenants, on the other hand, are informed that they will have the option to return to their estate after regeneration, but will have to pay higher rent. The rent on post-regeneration builds is set at levels closer to “affordable”, which is actually 80% of the market rate. “Affordable” houses are simply not affordable for most working people and therefore residents are often pushed towards the poverty line.

Poverty: Tenants who can afford to return and pay higher rent are not only left dissatisfied with the new living conditions, smaller homes and fewer garden spaces, but are also often forced into a hand-to-mouth existence.

One contributing factor to this is energy prices. Most recently, residents at Myatts Field, SE5, found themselves tied into a new communal energy contract that was introduced as part of the estate’s regeneration. Their energy bills skyrocketed and they are not able to opt out of the contract.

Fewer rights: Tenants who return also often do so with fewer rights, sometimes having their gold-standard “secure” tenancies replaced with new “assured” tenancies.

Death: Many vulnerable members of our communities, especially the elderly, do not survive eviction from their homes and their demolition. This outcome is usually related to their support structures being ripped from them in the name of progress.

These are not predictions or educated guesses about the effects of regeneration. They are realities that have been observed.

Residents do not benefit

When considering the above points it becomes apparent that asking residents why they oppose regeneration is like asking turkeys why they do not like Christmas. It is clear that residents do not benefit from the process – in fact, huge numbers of them suffer because of it.

Therefore we must ask who estate regeneration does benefit, if not residents and communities. By and large, the answer is, of course, developers and private investors.

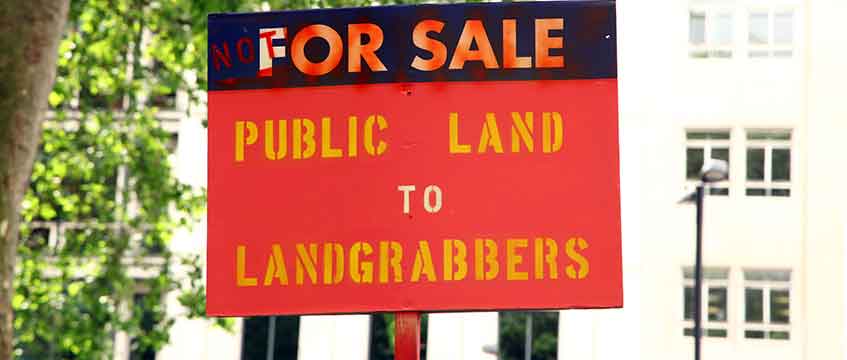

One line of defence often employed by councils proposing an estate redevelopment is that they are forced to sell public land and homes to replace funding streams that have been cut by central government. They argue that they have no other option.

Though I do not accept this justification, I do accept that councils now receive less funding and that government policy prevents councils from borrowing on a large scale. Unfortunately, instead of resisting cuts and pieces of devastating legislation such as the Housing Act, councils seek to bridge the funding shortfall elsewhere. This is where private developers come in.

Developers take full advantage of the political context within which many councils are increasingly forced to operate. They prey on the inability of councils to secure the level of finance required to lead their own public schemes, and extract a heavy price for their ability to access funding.

For the 2015-2016 financial year, the chairman of the Berkeley Group had a total annual remuneration package of £21.5m. Is his company’s level of profit justified by any particular display of entrepreneurship? No. Is its profit level justified by any notable innovation? No. Is it justified by any major level of risk? No. Developers take no risk whatsoever and yet dictate guaranteed returns that essentially result in the loss of council housing and truly affordable housing in this country.

Taxpayer funded, private sector exploited

This seems especially immoral when one considers that many of these estates were funded and owned by the taxpayer in the first place. I put it to you that any truly ethical developer would choose to operate only in the private sector and refuse to profit from the sale of public assets, at the expense of human life and communities of people.

Estate regeneration has been unjustified, unnecessary and unwanted. The fact that this debate starts from a point of a presumed need for regeneration, and seeks only to explore how best to demolish people’s homes, is in itself the problem with the process. There is no process. There is no democracy. There is just the foregone conclusion that our lives are worth less than prospective profit.

Our position is very clear. We will not accept the sale of our homes and the destruction of our communities while there are viable, affordable alternatives. We condemn the opportunist, exploitative role played by property developers and categorically oppose the transferral of public land into private hands. We demand that our councils resist applying the Housing Act. We demand that councils act in accordance with the wishes of residents, in a democratic manner.

We maintain that estate regeneration directly compromises the basic human rights of residents and we will fight to defend the rights of our friends and neighbours, to secure quality affordable housing – by any means necessary.

I imagine that councils and developers will assume that they have experienced the worst of our discontent. Quite the contrary. We have just been finding our feet. They have no idea what we have waiting for them just around the corner. We are ready to fight. Unlike them, we truly have no other option.

■ Click here to read the latest news from LREF

EG collaborators

EG is partnering with Mishcon de Reya and Mount Anvil to investigate how best to facilitate collaboration with an event in November and a bespoke magazine.

We will also be celebrating the best of the industry’s collaboratory efforts at the EG Awards in September. If you think you deserve to be recognised for a partnership or collaborative effort, click here to enter.