Paul Collins concludes his overview of the development process.

The design process starts from a moment in time when an opportunity is envisaged, however superficially, to the point in time when drawings, CGIs or models are complete.

It is normally the job of consulting architects, planners, quantity surveyors and development surveyors to work up a scheme’s design in order to get planning permission – but crucially, also, to meet expected design quality, cost budgets and projected completion times.

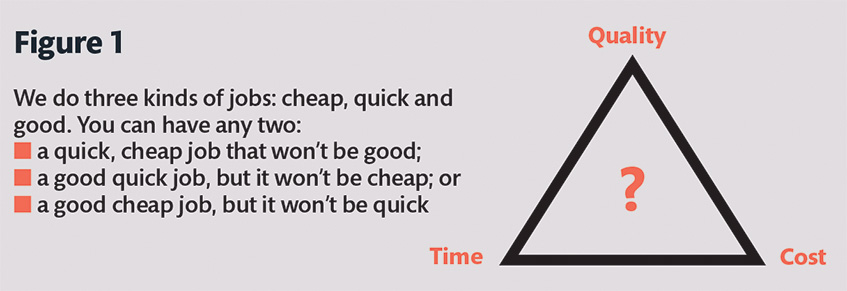

These three variables are always difficult to achieve, as making design quality the key criterion will impact on both costs and time (see figure 1).

Whatever the case, the following three factors are the basis of good design:

- the functionality and utility of a building’s spaces and places;

- the quality of its construction and materials; and

- that it is aesthetically good to look at and be in.

This was highlighted by Marcus Vitruvius, the Roman architect, engineer and surveyor in his Ten Books on Architecture, written circa 30-20BC, as restated in the 17th century by Sir Henry Wotton: “Well building hath three conditions: firmness, commodity and delight.” (See figure 2.)

This was highlighted by Marcus Vitruvius, the Roman architect, engineer and surveyor in his Ten Books on Architecture, written circa 30-20BC, as restated in the 17th century by Sir Henry Wotton: “Well building hath three conditions: firmness, commodity and delight.” (See figure 2.)

Sustainability

What about sustainability and the three criteria? While not explicitly dealt with in a modern sense, many historical buildings were designed with the climate in mind, in terms of material choices or orientation.

All new buildings today, however, have to meet fundamental sustainability criteria through the building regulations, but many developers aim higher by adopting technologies and approaches that meet higher non-governmental standards.

The Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM) rates the environmental credentials of proposed building types. Based on the number of credit points achieved, projects are assessed from outstanding to unclassified.

Find out more about this process at: https://bregroup.com.

Building regulations

In addition to planning permission, all new buildings (and alterations to existing ones) have to secure approval under the building regulations.

Their purpose is to ensure all new buildings, their refurbishments or changes of use are safe, healthy and perform well. Very wide-ranging, they cover all aspects of structural integrity, fire safety, accessibility, energy, and noise performance and building services.

They are updated from time to time as new threats or issues arise. As a result of the Grenfell Tower fire, for example, the government introduced an amendment in 2018, banning the use of combustible materials in the external walls of buildings above 18m that are used for residential purposes.

The regulations in England are set out across a range of matters, listed under an alphabetical index A-S with differences required between residential and other building use types.

What is important to understand is that they are legal rather than policy requirements.

The major English legislation governing them is the Building Act 1984. For those unfamiliar with the building regulations, it is important to realise they are very detailed and expert advice must always be sought.

More information about the building regulations in England can be found at: www.gov.uk/guidance/building-regulations-and-approved-documents-index.

Though listed differently, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland follow pretty well the same set of regulations:

- www.gov.scot/policies/building-standards/monitoring-improving-building-regulations

- www.gov.wales/building-regulations-approved-documents

- www.buildingcontrol-ni.com//assets/pdf/building-regulations-ni-2012.pdf

In terms of process, all building proposals (plans, specifications and materials, etc) have to be approved before building commences. Inspectors will then visit projects in progress and then finally on completion.

Appeals can be made with guidance provided on the respective government websites.

Construction procurement

A key decision for developers or corporate clients, is whether the detailed design and professional team work directly for them or for the contractor building the project.

These choices are part and parcel in choosing the right procurement strategy.

There are four main varieties of procurement for most projects:

- Traditional: This method involves the client directly employing architects, engineers, quantity surveyors and project managers to design, cost and time schedule a project, and then getting building contractors to bid for and undertake the work. It is called the “traditional” method in the UK, because historically, it has been the most common method of procurement. Today, it is typically used more where schemes are in some way complex, and more things need to be considered and determined by a client before making a commitment to build. Its key advantage is that it provides the most control over a project – but at the same time means the client carries more risk than other forms of procurement. In terms of practicalities, a project will be fully designed, and cost estimated, before being put out to tender.

- Construction management: This method involves the developer/client employing an architect and design team as in the traditional approach, but additionally a construction manager contractor (CMC) is appointed to oversee the whole project from start to finish in terms of quality, cost and time. What is important to note here is that while the CMC is contractually liable to the client, they do not have any contractual relationships with the contractors who actually build out a scheme.

- Management contracting: This approach appears similar to construction management, but the difference is in contractual relationships. The management contractor has a contractual relationship with the work contractors (ie the organisation that does the actual physical building work). This means, if things go wrong, the management contractor is responsible.

- Design and build: This approach involves getting building contractors to take responsibility for both the design and the construction of a project – and deliver it on time. This method of procurement is used more often for relatively straightforward development proposals. This means that the contractor will employ all of the design and construction team. In doing so, the approach passes much of the risk associated with this stage of the development process to the contractor. In part for this reason, the approach has increased in popularity over the last 25 years. In pursuing this approach, it is important that the client provides a clearly articulated design brief and expected performance standards. This will include floorspace requirement, facilities requirements, material qualities, external works, landscaping, and overall sustainability credentials.

- Design and build with novation: A variation of the above, is for the client to employ an architect to work up a concept design and associated specifications, then put out a design and build contract bid, but specify that the architect gets re-employed by the contractor to follow through the more detailed aspects of the design and specifications. This approach is called novating the architect (and other members of the professional team as appropriate). This has the advantage for the client of determining the desired concept but leaving the details to the contractor, but – importantly – the developer/client has no further control over the design team.

Marketing and selling

Marketing of any proposed scheme, if for sale or letting, while being discussed in this last part of the series, should take place both at the outset of a project and throughout the development process, not just when the buildings have been completed.

The marketing of any project starts (or should) at the very beginning of the process and continues through to final completion.

It is, as the Institute of Marketing’s definition suggests, “the management process responsible for identifying, anticipating and satisfying customer requirements profitably”.

The way a potential and final scheme is presented to a local authority requires good marketing skills, as does making the business case to banks and lenders, as well as to potential end user buyers, renters and – fundamentally – occupiers.

Successful marketing at its very basic level requires the right balance of the four key ingredients of product, place, price and promotion.

This also underlines that it is not simply about promotion and advertising. Getting the right balance between the four factors is the crucial challenge.

A great product (development scheme), with great promotion and at the right price, but in the wrong place, will be a hard sell or let.

Post-occupancy and post-completion development evaluation

Not carried out in practice as much as it should be, undertaking a formal post-occupancy evaluation to see if the scheme really meets the design objectives of the building for its users after a reasonable period of occupation is a valuable process. Doing this more often and sharing the outcomes across the industry is the way we can improve what we do and how we do it.

Standard practice, however, would be to compare the original business case and development appraisal (including budgetary targets and profit expectations) with outgoing results on completion, occupation and/or sale/letting.

The outcome of these two evaluations will be the measure of success – with a bonus icing on the cake if the press, professional critics or the general public hail the scheme a triumph (or at least are not overly critical of it).

Study tasks

Task 1: Think about the three criteria of functionality, quality and aesthetics, and undertake a critique of a range of existing buildings you know well, eg your place of living, university library or sports facility.

Task 2: Think about, list and explain the pros and cons for a client choosing the traditional versus a design and build approach. When complete, a helpful discussion of the pros and cons of the traditional versus design and build, can be found at:

https://urbanistarchitecture.co.uk/traditional-vs-design-and-build

Paul Collins is the editor of Mainly For Students and teaches at Nottingham Trent University