Christmas may be around the corner, but on Oxford Street, W1, the festive season will be very different. Long queues outside stores, a shortage of international tourists and the closure of some shops altogether are just a few of the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic for the area. For fans of the last-minute December shopping spree, it will just not be the same. Others may breathe a sigh of relief.

And although the pandemic-induced overhaul will most likely be a one-off, a decade of dramatic change could be ahead on Oxford Street. From pedestrianisation to a new set of names occupying its iconic stores, EG has asked the experts what they think London’s retail Mecca may look like in 10 years’ time – here’s what to expect.

All day I dream about shopping

The most immediate changes in the coming years will centre on Oxford Street’s star attraction: retailers.

The priority for dominant brands was once to cash in on the glut of tourists and shoppers the area attracts. But as consumers swap shops for screens, and online retail continues to outpace physical sales, this is increasingly thought to be an ineffective tactic. And that was before the pandemic.

Instead, a growing number of businesses hope to use the street as a place to advertise, rather than drive revenue directly, says Sam Foyle, co-head of Savills’ prime global retail team.

“For most [retailers], having four or five stores on the street is not really required now. Instead, what they have been looking at strategically is how to reposition themselves on Oxford Street to showcase their brand in the best way,” he says.

He points to Adidas as a prime example of what brands may do in the coming years. The sportswear giant last year opened a four-storey, 27,000 sq ft store opposite Selfridges, which it described as “more than a retail experience”. Foyle says the site is all about “showcasing their product, which will help them support their online and global presence throughout the rest of the UK”.

This could lead to a whole new breed of company flocking to Oxford Street, Foyle adds, including consumer brands such as car manufacturers looking to use the property as an advertising strategy. “Property can play a really important and pivotal role in brands engaging with a consumer,” he says.

Matthew Green, Conservative councillor for Westminster City Council, agrees, adding that these changes could be fundamental to bringing customers back to the high street after the pandemic as early as next year.

“The attention span of customers has grown much shorter, and one of the appeals of internet shopping is how nimble and how changeable it is,” he says. “So we need to make sure that the physical shopping experience has that same level of responsiveness.”

Speaking on Westminster Planning Association’s policy update webinar, Green adds: “You will see far fewer traditional high street stores or department stores [in 2030]. You will see many more concept stores, which will have an interactive element, more pop-ups, more smaller businesses working together to offer an experience.

“The retail of the future will be very immersive. That is what we want to achieve for Oxford Street, not just in 2030, but as early as 2021.”

Best foot forward

This could leave the street looking more like prime tourist destinations in Tokyo or New York, with digital signage and more prominent advertising across the board. But this would require Westminster Council’s consent.

“Oxford Street has historically lacked the planning authority to allow the brands to do these things,” Foyle says. “That is something we are going to need to see the council being more forward-thinking on over the course of the coming years.”

Meanwhile, down at street level, big changes could also be afoot. Plans are already in place for a part pedestrianisation of the area – but this could become even more far-reaching by 2030, says Jace Tyrrell, chief executive of the New West End Company.

“Whether it will be completely pedestrianised is unclear,” he says, adding that the street will probably always allow through-access for vehicles crossing from both the north and south sides, as well as for logistics purposes. “But we certainly want to be pedestrian-first. We have got to become a street that favours the pedestrian over all other uses.”

This could extend as far as making the entire region of Oxford Street, Regent’s Street and Bond Street a zero-emissions zone, Tyrrell continues, meaning that any vehicle that comes into the area would have to be electric. “That will be a game-changer for air quality,” he says.

The result would be unprecedented potential to make the street a more appealing public space – the need for which has been brought into sharp focus by the pandemic. “This will be a canvas for the very best of Britain,” says Tyrrell. “Whether it is the Royal Academy or a Banksy exhibition, we need to become a public promenade for Londoners and the world. That is what we need to deliver.”

Elad Eisenstein, Westminster City Council’s Oxford Street programme director, says: “From the international outreach of Oxford Street and unrivalled connectivity to the incredible diversity of local neighbourhoods with world-leading creative industries, garden squares, heritage and culture, our district has unique advantages.

“We are designing the city as an experience, and our strategy will place people at its heart – focused on creating a more attractive public realm which delivers health and wellbeing benefits, and leads to increased dwell time, social interaction and spend.”

The office upstairs

Banning cars and buses would make the area more of a draw not only for leisure purposes, but for office workers too. And with retailers re-evaluating the use of their stores on the street, a window could open for offices to be installed on the upper floors of many buildings.

Already John Lewis has obtained planning permission to convert some of its eight-storey store into office space. More could follow, says Hunter Booth, office agency director at Savills.

“If any of those buildings can create high-quality office space then there will be a market for it,” he says. “The question is really whether the likes of Debenhams and Marks & Spencer can deliver space that is of enough quality that you are able to get tenants to view it as a credible option.”

And although this would come with its own set of challenges – Oxford Street’s 1950s buildings are seen by many as far from optimal for office conversion – pedestrianising the streets below would go some way to making them attractive propositions.

“One of the criticisms of Oxford Street at the moment is it’s just bus after bus after bus,” Booth says. “Arriving to work via a pedestrianised street with no cars is much more attractive than dodging double-decker buses and breathing in all that before you arrive at the office.”

New look

Those looking for some indication of what the area could be heading for could look to Cavendish Square Gardens, just behind Oxford Street’s John Lewis.

The square’s huge underground car park is set to be transformed into a £150m subterranean wellness complex, which will house healthcare, office, entertainment, retail and leisure spaces over four storeys. Its proximity to Harley Street behind the development would make it a prime location for private specialists such as surgeons, dentists and doctors.

Most importantly, it hints at a vision for the area that incorporates more mixed-use spaces, rather than the retail hub that it is today, says Foyle. “[The Cavendish Square] development really will be a natural extension of Oxford Street,” he says. “That sort of space coming forward will be phenomenal.”

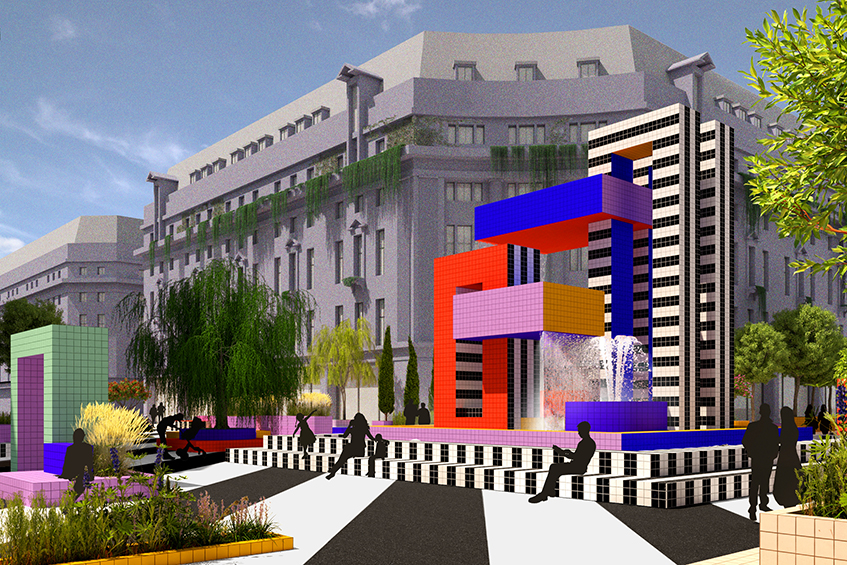

Others have made even more extreme proposals for the area. Artist Camille Walala, who recently repainted a row of shop fronts in east London as part of a £40,000 public art commission, last month released a selection of concept images of what Oxford Street could look like in future.

Her designs envision an area characterised by brightly coloured fountains, gardens and public spaces, built out of Lego-like blocks and decorated with bold stripes and patterns.

The proposals may look radical, but they are built on the same ideas being proposed to Westminster City Council now – namely, pedestrianising the street, freeing up planning laws and investing in public spaces.

Foyle agrees that such ideas would breathe some much-needed life into the street. “For Oxford Street to be a global leader in 10 years’ time, there needs to be much more investment in the placemaking on the street.

“Things like art installations, food stalls and entertainment would really change the vibe and the feel of the district,” he adds. “And more importantly, it would future-proof it for the next generation.”