Since the release of the consultation on biodiversity net gain in January, a lot has been said about the topic. This is no surprise. BNG concerns all developers, because it will become a mandatory planning requirement from November 2023 for most developments.

The majority of discussions about BNG focus on greenfield land (sites that haven’t been built on) as it is easier to understand how BNG works on them. However, a considerable amount of developments in the UK are on brownfield land (sites that have been previously built on), which is consistent with the NPPF as it provides that “Planning policies and decisions should […] give substantial weight to the value of using suitable brownfield land.”

How does BNG work on brownfield land? What happens to brownfield land where biodiversity returned while vacant or derelict? Here, we address these questions.

No BNG exemption

The December 2018 consultation on BNG evaluated an exemption for brownfield land. The government proposed a targeted exemption for sites that met a number of criteria, including that they: (i) do not contain priority habitats; and (ii) face genuine difficulties in delivering viable development. This exemption was issued in line with the preference in planning policy for reusing land that has been previously developed.

The January 2022 consultation dropped the exemption for brownfield land, because it would “deliver little added benefit and would greatly complicate the requirement’s scope for developers and planning authorities alike”. However, this consultation still proposes to exempt brownfield developments that exclusively involve the redevelopment of buildings on hardstanding or sealed surfaces.

As the exemption for brownfield land was dropped for most sites, then the BNG requirement applies to them. While at first sight the removal of this exemption appears to be a heavy blow for brownfield developments, a closer look shows a different story.

The hidden opportunity

The complexity of the BNG requirement depends on the biodiversity baseline. The Environment Act 2021 provides that, for the majority of cases, this baseline is the biodiversity existing on the “date on which the planning permission is granted”. On a greenfield site, no construction activities are allowed before the pre-commencement conditions of the planning permission are fulfilled, so the baseline is the untouched flora and fauna. On every brownfield site, construction activities have already taken place, so the baseline is the already reduced biodiversity after the original construction took place.

The current consultation considers that “many brownfield sites offer significant potential for achieving biodiversity net gain as they often have a low pre-development biodiversity value”. Owing to this potential, not only can they be used for development, but there is also a hidden opportunity in using them as generators of biodiversity units, which can be registered in a biodiversity gain site register and sold to other developers. The BNG requirement of one development can be achieved by purchasing biodiversity units from the market. Once BNG is implemented, many developers will be interested in buying biodiversity units.

Brownfield land developers have two options. First, develop the land. Second, if an economic evaluation shows that development is not viable, developers could consider implementing environmental remediation projects to generate biodiversity units. According to Environment Analyst, “biodiversity net gain could shake up the remediation market” – one hectare can yield several biodiversity units, which might be profitable as the market price is around £10,000-15,000 per biodiversity unit for a 30-year contract – and there might be potential to obtain additional income from other natural capital benefits (ie carbon offsetting, flood mitigation, water purification and green energy generation).

Biodiversity Metric 3.0

The analysis above is based on the assumption that the pre-development biodiversity of brownfield land is low. However, this might not always be the case.

In July 2021, Natural England launched Biodiversity Metric 3.0, which, subject to further consultation, is expected to be the metric specified for mandatory BNG. The metric uses “habitats” as a proxy for biodiversity, which, as Natural England concedes, is a simplification of the real world as this tool was designed only to measure the relative worth of one scenario against another. Identifying the correct habitat is of major importance, because the values assigned to each habitat can differ greatly and there are no in-betweens between habitats.

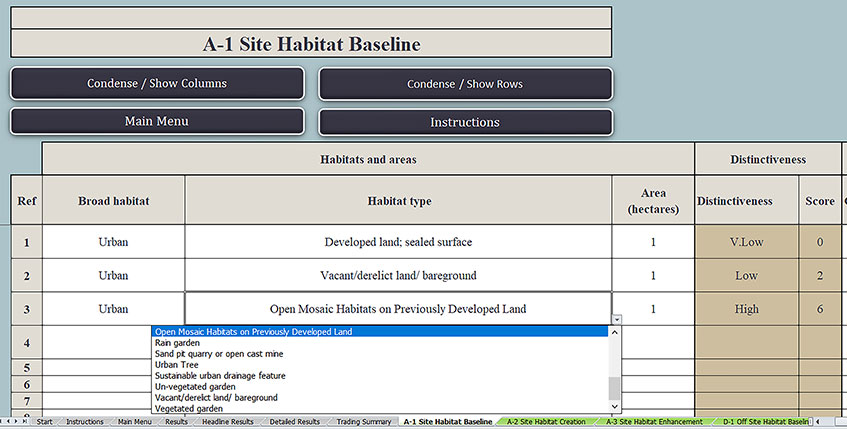

For calculating the biodiversity baseline, the metric offers drop-down lists from which one must select the habitat type, its condition and its strategic significance. The baseline value (referred to as “habitat units”) is calculated automatically after all options are selected. This is most easily explained by the screenshot and explanation below.

Source: Natural England’s Biodiversity Metric 3.0 – Calculation Tool, found here

The hidden risk

The habitat corresponding to a site depends entirely on the specific characteristics of the site. Therefore, there is not a single habitat applicable to all brownfield land. However, in our opinion, the following habitats from the drop-down list are the most suitable for brownfield land:

- Developed land; sealed surface;

- Vacant/derelict land/bareground; and

- Open mosaic habitats on previously developed land (OMHPDL).

“Developed land; sealed surface” has a “very low” distinctiveness (multiplier 0), which is consistent with the BNG exemption for developments over sealed surfaces. The multiplier is zero, so the biodiversity baseline is always zero.

“Vacant/derelict land/bareground” predictably has a “low” distinctiveness (multiplier 2). This is the lowest multiplier for habitats not exempt from the BNG requirement. Brownfield land that fits in this category can be used as a bank of biodiversity units.

The habitats above fit with the regular conception of brownfield land as barren of biodiversity. However, nature usually takes over brownfield land left untouched for a prolonged period of time. What habitat type applies to these sites?

Here lies the hidden risk on brownfield land (for the purpose of complying with BNG). If the site has developed enough biodiversity to qualify as grassland, wetland or other habitats, then it will be considered as such. Alternatively, sites populated sparsely by biodiversity might be considered as OMHPDL, which surprisingly was given a “high” distinctiveness (multiplier 6). This is the second-highest multiplier available in the metric and, for comparison, is also given to some types of pristine grasslands. For that reason, it will be substantially harder to use brownfield land in this category as a bank of biodiversity units.

What is an OMHPDL? In the words of NatureScot, it consists of a patchwork of bare, previously disturbed ground and stands of vegetation which can be in the process of changing from one vegetation type to another. This habitat was added to the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (UK BAP) as a priority habitat listed under section 41 of the Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006.

The Joint Nature Conservation Committee uses five criteria for guidance to determine if an area qualifies as OMHPDL.

Criteria

- The area of open mosaic habitat is at least 0.25ha in size.

- Known history of disturbance at the site or evidence that soil has been removed or severely modified by previous use(s) of the site. Extraneous materials/substrates such as industrial spoil may have been added.

- The site contains some vegetation. This will comprise early successional communities consisting mainly of stress-tolerant species (eg indicative of low nutrient status or drought). Early successional communities are composed of (a) annuals, or (b) mosses/liverworts, or (c) lichens, or (d) ruderals, or (e) inundation species, or (f) open grassland, or (g) flower-rich grassland, or (h) heathland.

- The site contains unvegetated, loose bare substrate and pools may be present.

- The site shows spatial variation, forming a mosaic of one or more of the early successional communities (a)-(h) above (criterion 3) plus bare substrate, within 0.25ha.

While determining which habitat corresponds to a site can only be done with a case-by-case evaluation, it does not seem exceedingly difficult for large brownfield sites with some biodiversity to comply with the criteria above for OMHPDL.

Final word

Brownfield land is not exempt from the BNG requirement, so any development must guarantee a 10% increase in biodiversity.

Brownfield land with low pre-development biodiversity has a significant potential for achieving BNG. If a development is not economically viable, developers have the alternative opportunity to implement environmental remediation projects and use the brownfield land as a bank of biodiversity units, which can be sold in the market, and obtain additional income from other natural capital benefits.

However, not all brownfield land has low pre-development biodiversity. There is a risk that some sites will qualify as habitats with higher biodiversity value, and even sites with sparse biodiversity could be considered as OMHPDL. The complexity of complying with the BNG requirement on brownfield land will depend on the type of habitat existing on the site. Brownfield land qualified as OMHPDL will have a biodiversity baseline three times higher than that with similar conditions but qualified as vacant/derelict land/bareground.

Developers will need to take this into consideration when carrying out the economic assessment before starting a development or improving the environment on the site to obtain biodiversity units for sale.

Stefano D’Ambrosio is a solicitor in the planning and environment team at Irwin Mitchell